By Jonathan Berg

Our walking tours of Birmingham tell of the development of

the city from our medieval past to where we are heading in

the 21st Century. We include open and honest discussions

about our city and certainly, the more murky aspects of the

Industrial and Commercial Revolutions in the 17th and 18th

centuries will be more to the fore on future tours. Modern

interpretations of Birmingham’s historical development have

tended to gloss over the more unsavoury aspects. When we

look at our history with new eyes, things are revealed that

certainly do not fit the ‘easy read’ of an entrepreneurial

environment which became the ‘town of a thousand trades’.

Yes, the simplistic history we often tell sees Birmingham

starting as a market town in medieval times. Using

ingenuity, local Black Country raw materials, and power from

water-mills Birmingham developed production skills and

made things people wanted such as ceramics, leather, and

then metal items. In the 18th century, we became a major

centre of the Industrial Revolution. The explosive growth of

the town caused all sorts of issues that our famous Mayor

Joseph Chamberlain and his Victorian mates sorted out for

us from the 1870s. Our stories tend not to dwell on the darker

sides of our roles in colonial development and links with the

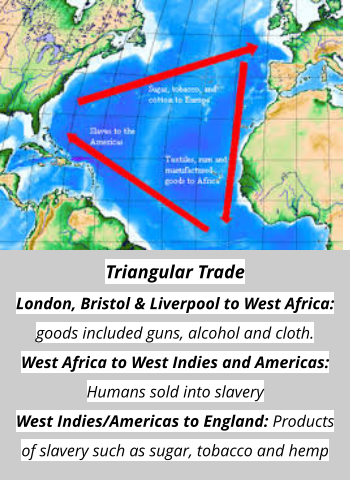

slave trade hardly get a mention. After all, as we learned in

history lessons at school, the Commercial Revolution of the

17th and 18th centuries was centred on a trade triangulation

based on the ports of London, Bristol & Liverpool with West

Africa and the Americas. Produce went to Africa, slaves on to

the West Indies and the Americas. Goods such as sugar,

hemp, tobacco, and rum came back to England….job done.

There is never a mention of Birmingham.

We recognise that Birmingham’s production of knives, guns,

and more general armaments and wartime materials have

been important from medieval wars right up to the 20th

century. However, instead of gun production, for which

Birmingham and the Black Country were hugely involved in

the mid-1700s, we prefer stories of James Watt and his steam

engines and the town’s manufacture of buttons and buckles,

pen nibs and even celebrated Victorian whistles still made

today on the original fly presses.

The Black Lives Matter campaign has changed this forever. It

has fuelled a desire for us to understand more of our past

and ensure the stories we tell give a balanced and less

superficial view. The result is an appreciation of the way the

past is sometimes sanitized for the sake of a happy ‘touristy’

experience; because of course considering the more difficult

aspects of our history is just that…difficult, at a number of

levels! So, let’s get on with it.

Farmer’s Flight … what’s in a

name?

I love our full of surprises Sunday afternoon walking tour. It

heads down the ‘secret canal’ to the Jewellery Quarter,

looking at the development of different aspects of the

historical ‘toy’ industry and shows how the coming of the

canals was so important in bringing the raw materials

needed for the huge expansion in manufacturing. From sole

trader artisans working at a rented ‘peg’, to medium-sized

family business such as Newman Brothers and their brass

works specialising in coffin fittings. Finally, huge industries

moving fast to take ideas and inventions into world-scale

production at an amazing pace. This is a fascinating and

exciting story, and we wonder why the whole of Birmingham

does not want to walk with us! We learn so much about the

successful enterprises that started the Industrial Revolution

and were built upon by Victorian businessmen. The story just

unfolds all around us as we walk. As a tour guide I get a feel

for the way business, even in today’s city, is to an extent

rooted in our past with a ‘got a new idea….come and do it

here’ approach to life.

Researching the tour to the Jewellery Quarter we wanted to

gain an understanding of the Farmer family whose name is

given to the canal flight we walk alongside. The Farmers

were co-owners of Birmingham’s largest 18th Century gun-

making company. Joseph Farmer came to live in Old Square

from Bristol in 1702 and set about manufacturing steel wares

including gun lock springs, sword blades, gun barrels, and

boring tools. His son James took over the family firm and in

1746 his brother-in-law Samuel Galton joined him from

Bristol to help take their business forward.

Moving to London is never

recommended!

Perhaps success went to his head as James Farmer made

some mistakes. First, he left Birmingham and moved to

London – something we always advise on tour is a sign of

poor judgment! Secondly, in London, it did not take him long

to go bankrupt, though he was well protected by fellow

Quaker bankers and soon re-entered Birmingham’s gun-

making business. The ‘letter books’ of the Galton and Farmer

firm are in the Library of Birmingham archives and give an

insight into a company working right at the start of the

Industrial Revolution. Today these also tell much about the

role of Birmingham guns in the slave trade. These archive

materials have been used for several major pieces of

research, with an MSc back in 1972 by one W. A. Richards.

More recently ‘Empire of Guns’ is a mighty work by Priya

Satia, Professor of British History at Stanford University,

which takes the Farmer and Galton company as primary

evidence of the central role of Birmingham businesses in the

slave trade.

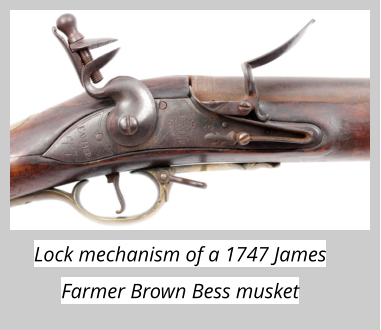

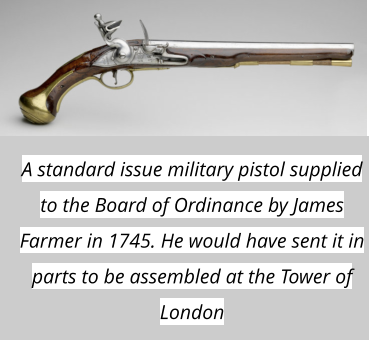

Farmer and Galton’s main gun factory in Steelhouse Lane

became the largest of the Birmingham gun makers. This was

and indeed remains, as it still goes on a little in today’s city, a

complex trade, with many components manufactured by

subcontractors in small workshops in Birmingham and the

Black Country. For example, locks were made in Wednesfield

and springs in West Bromwich. Wednesbury became a

centre for gun barrels which lead to expertise in tubing

manufacture still retained today. The complexity of multiple

gun designs was to an extent overcome with standard

component designs demanded by the Royal Ordinance and

the advent of variations of the Brown Bess musket design

which came in various forms and lasted over 100 years. On

top of all this was the complexity of competing with the

protectionist London gun makers. Marketing and sales were

complex, with very different customers from the

Government right through to slave ship captains who

fancied making some private side-deals alongside his major

cargoes.

Guns for the African trade

At times of war demand for Birmingham guns were high,

with orders from the Royal Ordinance to keep up their stock

in the Tower of London and arm multiple wars. In between

wartime production things were difficult for the

Birmingham trade, and supplying arms to West Africa

became hugely important. In 1752 Farmer and Galton were

producing 12,000 guns a year for the African trade and by

1754 the company was overrun with orders and trying to

produce 600 guns a week. Around 50% of production

headed to Liverpool to ‘fit-out’ slave-trading boats with

estimates that 200,000 Birmingham guns a year were being

sent to West Africa alone.

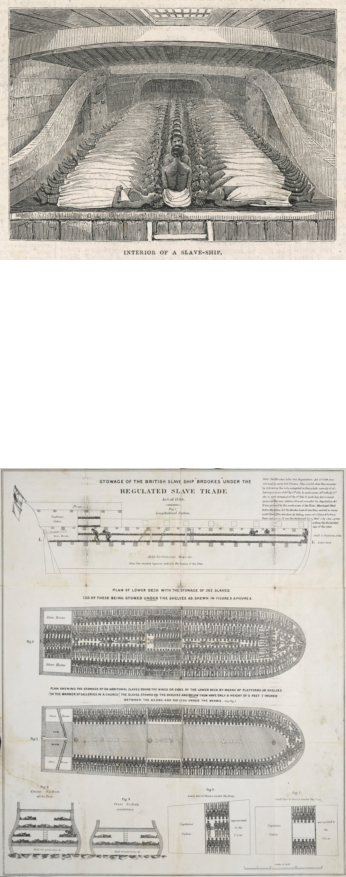

When the guns arrived in African ports along with

Manchester cotton cloth and other products they were used

in place of money to trade for the slaves supplied by African

tribal leaders. Put simply Birmingham guns were directly

exchanged for human beings who had been rounded up to

be sold into slavery. No one can deny that Farmer and

Galton’s origins, growth, and sales were deeply rooted in the

slave trade. The firm was the chief supplier to the formal

African Company and also a range of private merchants.

‘Empire of Guns’ eloquently argues that Birmingham guns

were used as money to pay for the slaves and fundamental

to both the Commercial and Industrial Revolutions.

Attitudes to abolition are key

It is attitudes to the abolition movement that is perhaps the

most revealing. The different views and actions of the Lunar

Society members as the movement grew is of interest.

Samuel Galton Junior (1753-1832) took the gun making

business forward from his father and was one of the younger

members of the Lunar Society which were divided in opinion

regarding the abolition of the slave trade. By the 1790s the

Lunar Society had both abolitionists and those seemingly

more ambivalent with their businesses still inextricably

linked with the slave trade. In ’The Lunar Men’ Jenny Uglow

gently brings out differences in the group. She shows

Thomas Day as an early abolition campaigner with his 1773

poem The ‘Dying Negro’ recalling an African slave awaking

from sleep on board a slave ship and saying:

‘I woke to bondage and ignoble pains

And all the horrors of a life in chains.’

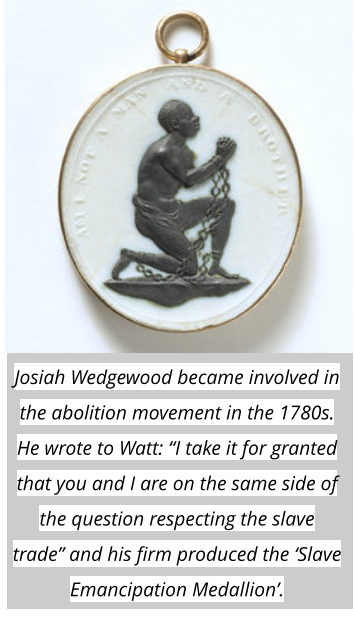

Josiah Wedgwood also comes out as a strong abolitionist

and even checked out the support of other Lunar Society

members, once writing to James Watt and directly

challenging him on his position.

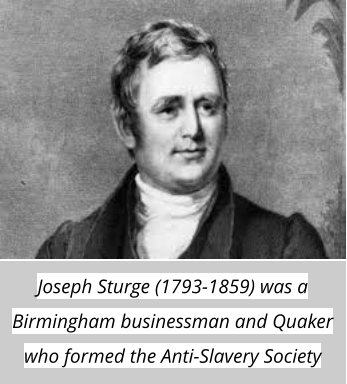

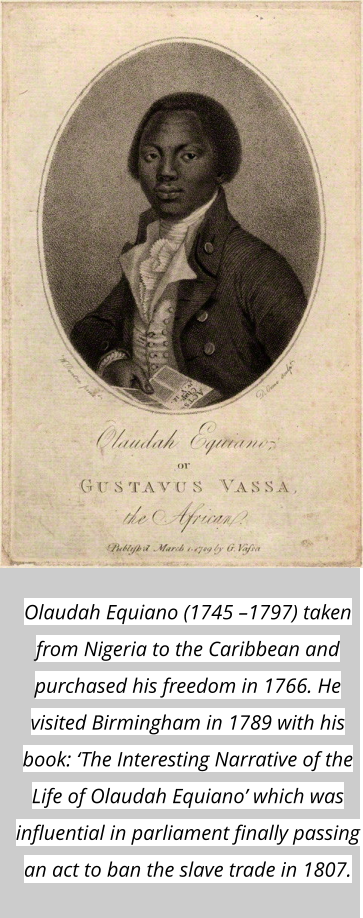

In 1789 Olaudah Equiano visited Birmingham to promote his

antislavery autobiography called ‘An Interesting Life’. He was

welcomed by Lunar Society members Galton, Boulton, and

Priestley. However, the visit did not stop Boulton & Watt from

working up deals with Liverpool slave trader John Dawson to

supply steam engines to Trinidad.

Poor quality Birmingham guns

ridiculed

A section of Birmingham industrialists certainly petitioned

parliament against abolition. One reason given by the gun

making lobbyists was that they would lose markets for the

guns that failed to proof and were turned down by the Royal

Ordinance. This caused controversy and a Board of Trade

inquiry in 1790 heard that the poor quality Birmingham

guns: ‘Kill more out of the butt, than the muzzle’. To

suggestions that Birmingham gun makers dumped proof

failed guns to the African market, the gun makers retorted

somewhat weakly that the Africans loaded too much

powder! Luckily the guns sold to Africa were used more for

showing wealth and as part of funeral customs than as state

of the art weapons. In tribal wars, the guns were there but

blades were the weapon of choice. Indeed the guns sold to

Africa were of such poor quality that exports were still

allowed at times of war. When Galton had a shipment seized

he successfully argued that they were simply ‘trade guns for

Africa, not arms’.

The abolition movement had turned the tables, with poor

quality and dangerous Birmingham ‘trade guns’ becoming a

scandal as they ‘burst when fired and mangle the person

that has purchased them’.

Currency not guns…

The guns sold to West Africa from England are estimated at

150,000-200,000 a year in the latter part of the 18th century.

Their use as a currency was seen across the Empire with the

lack of local currency meaning that items such as sugar

tobacco and other goods were bartered. Birmingham brass

wire was also popular as currency and wire made in

Birmingham ended up as ‘Guinea rods’. In return gold and

silver as well as cotton and indigo and alcohol were all

commodities traded instead of money.

The lack of currency around the colonial world, while partially

overcome by bartering was a barrier to efficient trade. This

was something that one of our ‘Golden Boys’ Matthew

Boulton spent the last thirty years of his industrial career

doing something about. Boulton set up the Soho Mint

alongside his manufactory to address the lack of coinage

both at home and abroad. He had to pay his workers with

money that was often of dubious origin, with the majority of

halfpenny pieces in circulation being forgeries often

produced in Birmingham’s back streets. Boulton coupled the

new James Watt’s rotatory steam engine with precise and

fast coining presses that would revolutionise coin production

for the world. Boulton’s coining adventure has clear links

with gun makers, the Galtons and others helping with

technical expertise and collaboration.

While he petitioned parliament to produce coins of the

Realm he had to wait until 1797 to get his first contract for

George III pennies. In the meantime, he produced tokens

and then coins for customers from around the world. His first

contract was an order for the East India Company for

Sumatran coins where the company had major interests in

spice works with workforces of slaves.

On our walking tours, we stand by the statue of Boulton,

Watt and Murdoch, (or a poster of it while it is in store), using

it to describe the origins of the industrial revolution and the

manufacture of small metal items known as Birmingham

‘toys’. These three gilded gents have acted until now as a

reminder of our industrial roots. We explain that Boulton, the

son of a small-town toy manufacturer, thought big and

produced a large scale manufactory by a water wheel at

Hockley Brook. His entrepreneurial skills and working

practices were certainly formative in the way Birmingham

approached life, perhaps even to this day. He funded

businesses with multiple partners and not one but two

dowries from the Robinson sisters from Lichfield. When it

suited he ruthlessly dropped partners and moved on. He

spotted opportunities, such as the world-beating steam

engine design and manufacturing, persuading James Watt

to come and join him in Birmingham to ‘power the world’.

He was astute enough to see the importance of political

decisions on his businesses. Directly or through

intermediaries he exerted his influence on Parliament to

help with projects as diverse as routes for a new canal from

the Black Country and the establishment of an assay office

for Birmingham.

Of course, these Georgian industrialists that we so revere

today lived in times where commercial and industrial

development was interlinked with the expansionist activities

of the wider nation. Birmingham business could hardly avoid

being involved in the slave trade as it supplied much-needed

goods for the colonialists’ across the developing world. We

know that James Watt senior was involved with the slave

trade with his activities at the Scottish port of Greenock. As a

young man James is recorded as selling at least one

imported slave to a country house and it is suggested

funding for his training as an instrument maker in London

came from the proceeds of slavery. Meanwhile, Matthew

Boulton certainly entertained those employing slaves in the

West Indies at Soho and this culminated in the purchase of

over 120 steam engines for use in sugar cane plantations

with export starting in 1803. While some suggest that the

Boulton family archives have been sanitized there remains

evidence that Bouton’s businesses were involved with

contracts to slave traders.

‘Golden Boys’ reflect on different

times

To see the statue of slave trader Edward Colston pitched into

Bristol’s floating harbour was certainly a dramatic moment

in the Black Lives Matter campaign. What then of

Birmingham’s memorials and pointers to historical links to

the slave trade in today’s city? Certainly, Farmer’s Flight

should be used to open up a discussion on the role that the

Birmingham gun trade played in supporting the slave trade.

Renaming the flight of locks or keeping the name serve

equally as a basis for Sunday afternoon and weekday school

group discussion on roles of Birmingham in things of which

we are not proud.

What to do about the much loved ‘Golden Boys’ statue of

Boulton, Watt and Murdoch to be placed on a brand new

plinth outside an extended Symphony Hall later in 2020

beside the modernism of the reflective pool? Certainly, we

will use the statue to look at the huge advances during the

so-called ‘Age of Enlightenment’ that these pioneers of the

Industrial Revolution represent. However, we will also point

to the Boulton & Watt business dealings with both gun

makers and slavers, and the production of hundreds of

steam engines for West Indies’ sugar plantations, and what

of complex interactions with the provision of coinage with

contracts with slave trading companies.

Much to consider as we walk this

city

No longer will we introduce the ‘Golden Boys’ as “the non-

controversial statue in Centenary Square” contrasting it to ‘A

real Birmingham family’, Gillian Wearing’s impressive study

of contemporary family life in the city. Yes, the ‘Golden Boys’

statue will now open up a different discussion than perhaps

William Bloye envisaged when it came out of his Small

Heath factory in 1956.

Black Lives Matter is confronting our interpretation of

Birmingham’s history and this can only be good for us all as

we work to take one of Europe’s most progressive and

exciting multicultural cities into the future.

Comments welcome: info@positivelybirmingham.co.uk

Other websources on Birmingham and the slave trade:

•

BBC article: ‘Abolition - did Birmingham profit?’ Read

here……

•

History West Midlands podcast: James Watt and

slavery: The untold story. Dr Malcom Dick talks to Dr

Stephen Mullen, looking in detail at slave trade links of

the Watt family. Stephen concludes that the profits of

slavery can influence industrial development in ways

not at first obvious and that we should take more note

of slave trade links of ‘dead white men that we celebrate

still today’. Listen here…..

•

The Birmingham gun manufactory of Farmer and

Galton and the slave trade in the eighteenth century.

Richards W.A, MA thesis abstract - University of

Birmingham. Full thesis PDF available upon request.

Read here…..

A not so pretty story:

Birmingham and the Slave Trade